In the study of economics, understanding individual incentives is critical to understanding motivation, decision making, and economic outcomes. At the decision point, understanding one’s “locus of control” and related psychology is the key to unlocking an individual’s rational mindset. Decision support solutions can be a big help to bring together people with differing psychology, differing professional judgments and for the purpose of driving optimal and efficient decisions.

This is Part II of a three-part series.

(Please click the boxes for the other article sections.)

The Train Thought Experiment

To help illustrate the locus of control and related psychology impact, we present the following train narrative as a thought experiment.

Imagine there are several trains that go around the entire earth. They are slow trains, your train trip will take about 30-50 years. The train tracks are equipped to go on land, over mountains, and across oceans. The trains are fully apportioned to allow people to live on them for the trip duration. Once you get to your destination, a substantial amount of money will be given to you or will be available to whomever you wish to give the money. The following are a few rules about the trains:

- You must choose a particular train at the beginning of your journey.

- Your train choices maybe limited, with limited information, and maybe randomly biased.

- Once on a train, you have limited ability to change trains.

- After the train departs the station, you and all the other people on the train will need to earn roles. Those roles could be as a conductor, an engineer, a trainperson, a fireperson, a passenger assistant, a dining person, etc.

- Each role has different responsibilities and pays different amounts of money. The role choices are designated as voted by all the people on your train. The voting process maybe randomly biased.

- While the roles get paid different amounts of money during the trip, the big payout occurs at the end of the trip. If you do not get to the end of the trip, there is no big payout. All the participants receive a similar big payout amount.

- Periodically, the train will have to switch tracks. Some tracks lead to a dead end, other tracks will continue toward your destination and may even get you to your destination faster.

- You have limited information as to the best switch track. Sometimes, you will not have the choice of certain switch tracks.

- The roles described earlier will have differing levels of control over the track switching decision. The conductor has the most say over the track switching decision. Level of decision control generally declines as consistent with the role order presented earlier in 4.

So what would you do? What train information would you request to make a decision and why? Once aboard your chosen train, which role would you choose and why?

It is clear, getting to the destination is most important from a payout perspective. So, you may ask questions that help you understand which train provides the highest risk adjusted probability to make it to the destination. But, the potential random bias uncertainty is troubling.

From a role decision standpoint, there are two kinds of roles, “easy”-based and “impact”-based.

- Perhaps choosing an “easy” role with less decision making responsibility would make sense. You appear to have little control over getting to the destination and you may worry about how random bias will effect your ability to make a difference. Or,

- Perhaps, choosing the “impact” role that gives you some track switching control may help you and your other train mates get to the destination. Even though you have little control, someone needs to make decisions, even though those decisions may not matter.

As you have probably figured out as we discussed in Part 1, “easy” relates to an external locus of control and “impact” relates to an internal locus of control. Also, please notice the more you learn about the system, the more you realize you have less control over the system.

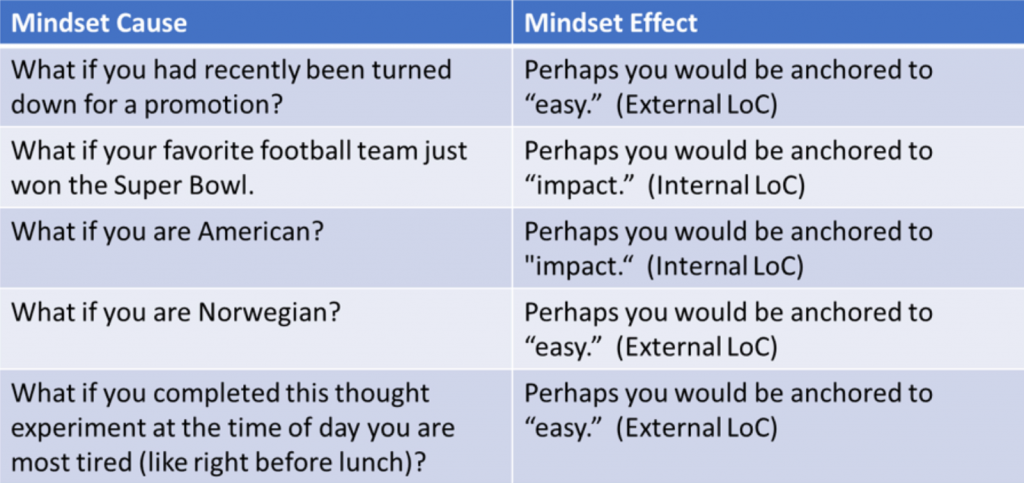

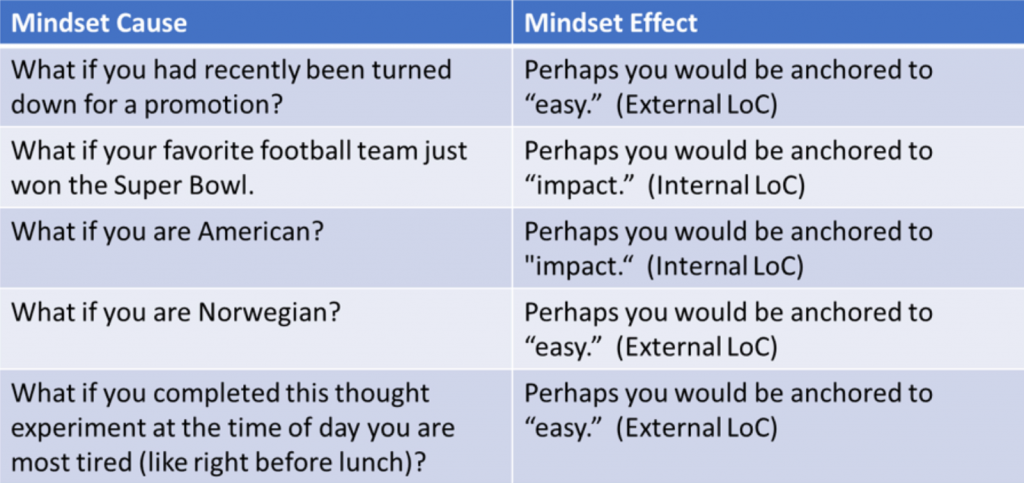

It is likely your local individual and cultural mindset matters greatly when completing this thought experiment. For example:

Please follow the link at the top of the article for additional sections.

For more information, please contact Definitive Business Solutions, Inc.:

- John Sammarco, President | JSammarco@DefinitiveInc.com

- Jeff Hulett, Executive Vice President | JHulett@DefinitiveInc.com

Notes:

- John Muth (1961) Rational Expectations Theory. The theory was more extensively utilized in macroeconomics by Robert Lucas.

- Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky (1979). Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk. The theory demonstrates how people are asymmetric in how they react to loss aversion. It also shows how psychological anchoring can impact this reaction. Daniel Kahneman earned a Nobel Prize as a result of this theory and work related to the integration of psychology and economics.

- Julian B Rotter (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement

- Daniel Kahneman, Cass Sunstein, and Olivier Sibony (2021) Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment. The 4 listed gap types are related to noise archetypes described in Noise. They are Level Noise, Stable Pattern Noise, and Occasion Noise. When comparing bias and noise, the authors make a powerful case that noise is far more impactful and difficult to manage in the decision-making process. A more fulsome explanation is provided in: Jeffrey Hulett (2021) Good decision-making and financial services: The surprising impact of bias and noise.

- Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein (2008) Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness

- Thomas L. Saaty (1982) Decision Making for Leaders: The Analytic Hierarchy Process for Decisions in a Complex World

- Definitive Business Solutions, Inc. designed and integrated a bespoke solver engine, utilizing a number of solver programing code sets and data transmission capabilities, uniquely needed for the AHP and cloud environment.

© 2021 Definitive Business Solutions. All Rights Reserved.